ISRAEL IN EGYPT: HANDEL's BORROWINGS

No piece better illustrates Handel's practice of recycling musical materials — from his own works, and above all from those by other composers — than Israel in Egypt. Of the thirty-five orchestral movements we perform this week, fully twenty draw on pre-existing works. (The original Part One, 'The sons of Israel do mourn', which Handel cut after the first performance, was itself a reworking of Handel's Funeral Anthem for Queen Caroline, The ways of Zion do mourn, HWV 264).

This page aims to give you the clearest possible idea of Handel's 'borrowings' in Israel in Egypt. As you scroll down, you will be able to see the source works and Handel's versions presented side-by-side.

but isn't 'borrowing' plagiarism?

In a world where pop singers take one another to court for perceived similarities between melodies or trivial chord progressions, Handel's wholesale appropriation of music by others doesn't look good. But our modern concept of originality is essentially a nineteenth-century construct, and attitudes in the Baroque era were rather more fluid. Perhaps more interesting than trying to take an anachronous ethical position is to consider the reasons why Handel might have wanted to borrow, the sources which he mined, and whether there could be any larger meaning underlying his choices.

reasons to borrow

All sorts of suggestions have been put forward to try to 'justify' Handel's methods to modern eyes. He was (as usual) writing in a hurry: the whole piece was composed between 1 October and 1 November 1738. But in many cases, it seems likely that adapting music written for different forces might well have been more time-consuming than starting from scratch! Some have claimed that he needed some sort of compositional crutch to get himself going, or that his powers of imagination were fading. None of this seems plausible to me. Rather, I am drawn to the arguments of Ellen T. Harris, which are worth quoting at length:

"As terrifying as it may seem, we need to reach for Handel's intentions and to look for meaning. Asking ourselves over and over whether Handel borrowed more or less than contemporary composers and whether contemporary audiences were aware of the borrowing and ultimately whether Handel maintained his morality as a composer will bring us no nearer an understanding of whether Handel was a great artist. The questions should rather be whether the borrowings are important to the content of Handel's compositions — whether they add to or are merely superficial to the content. Instead of wallowing in self-pity, we need to ask what Handel borrowed when... When is the borrowing clearly cued by text? In short, to what are the borrowings personally meaningful to Handel?"

(from Ellen T Smith: "Integrity and Improvisation in the Music of Handel", The Journal of Musicology , Summer, 1990, Vol. 8, No. 3 pp. 301-315)

handel's sources

Handel makes extensive use of two large-scale pieces by Italian composers:

Qual prodigio é ch’io miri, a wedding serenata by Alessandro Stradella (1643-1682)

Magnificat by Dionigi Erba (1692-1730)

He also borrows from a Te Deum by Francesco Antonio Urio (1631/2-c.1719), which is also a major source for Saul and the Dettingen Te Deum; from Canzona 4 by J.C. Kerll (1627-1693); an organ Capriccio über den Choral 'Ich dank dir schon durch deinen Sohn' by N.A. Strungk (c.1640-1700); the Ricercar sopra 'Re fa mi don' by Giovanni Gabrieli (c.1554-1612) and from several of his own works: the keyboard fugues HWV605 and HWV609, 'Tu es sacerdos' from Dixit Dominus, and an aria from his Chandos Anthem The Lord is my light. I have also seen it stated that he draws from Zachow and even from Rameau, but I haven't been able to substantiate this.

Clicking on the titles above will open the score of each work, but lower down this page I show side-by-side comparisons.

It is striking that these composers are nearly all from a generation before Handel, and in some cases considerably earlier than that. Perhaps in aiming for a certain 'antique' colour in his musical materials, Handel seeks to reflect the Old Testament antiquity of this story. But it's also interesting that in the second part of Israel in Egypt, which recounts Moses' song of praise, Handel draws extensively another song of praise, this time offered by Mary, in the shape of Erba's Magnificat. There are several felicitous textual similarities between the two, as we will see. But is Handel emphasising a theological point here — that the Old Testament story of redemption represented by the Exodus narrative is mirrored by the New Testament redemption offered by Mary's son? The quotation from the Lutheran Easter chorale 'Christ lag in Todesbanden' in the opening chorus of the work (if indeed it is intentional) seems to serve a similar purpose: Easter, for Christians, takes the place of Passover (which celebrates the Exodus), with Christ as the Paschal lamb.

Theology aside, I find it remarkable that Israel in Egypt adds up to such a wonderfully coherent whole, despite Handel drawing on this eclectic range of source material. His artistry and alchemy in combining newly written music with his deft (and sometimes transformative) reworkings of his 'found materials' are extraordinary.

The table below shows which movements borrow from which works. In some cases the borrowings are limited - a few bars; in other cases they are far more thorough-going. Read on for a more detailed analysis!

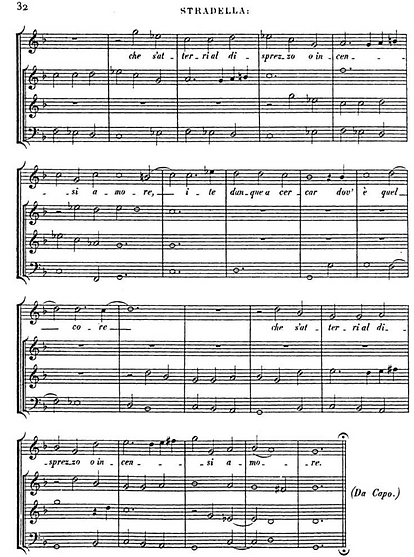

stradella's serenata

Alessandro Stradella led a remarkably colourful life, working first in Rome where he tried to embezzle money from the church and became notorious for his incautious affairs with women. He then went to Venice as music teacher to the mistress of a nobleman; he began an affair with her and fled to Turin, where his employer's men tried to kill him. He was finally murdered in 1682 in Genoa, probably as a result of another affair.

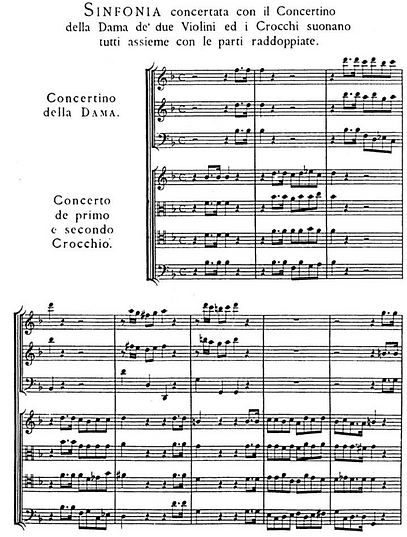

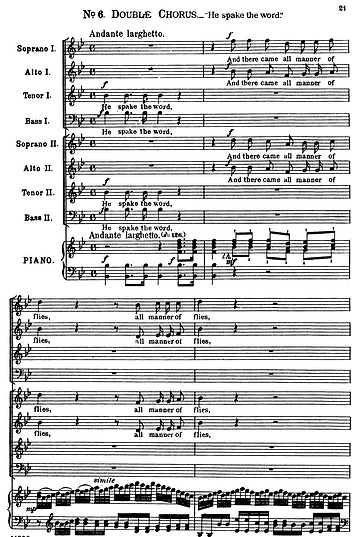

Handel draws on Stradella's Serenata in five movements of Israel in Egypt. The first appearance is in no.6, which reworks a Stradella instrumental Sinfonia. The borrowing extends to almost the entire movement, but the scurrying music for the fleas is Handel's invention.

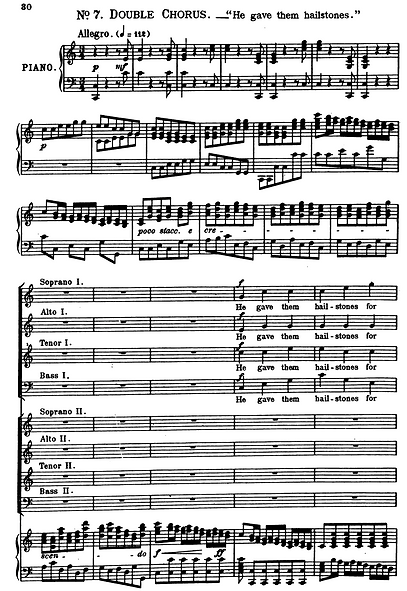

The introduction to the next movement, no. 7, combines Stradella's opening Sinfonia with music from a bass aria, though the antiphonal voice parts are Handel's.

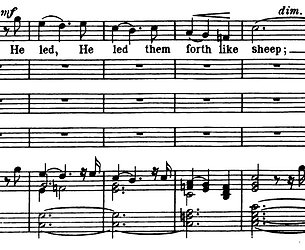

In Handel's no.10, the beautiful falling motif 'He led them forth like sheep' is drawn from a suitably pastoral Stradella aria:

However, the central contrapuntal section of the chorus draws extensively on another piece entirely: an organ work by Nicolaus Adam Strungk, who worked in Hanover, Dresden and Leipzig in the later seventeenth century.

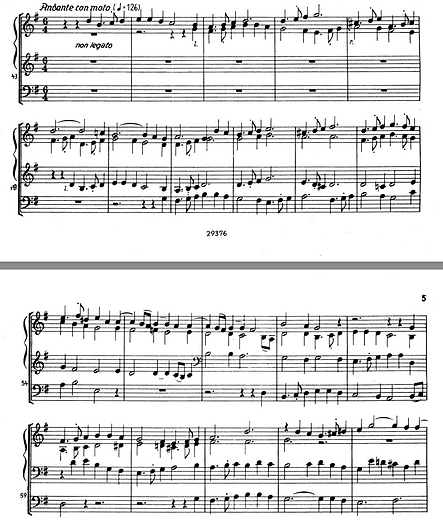

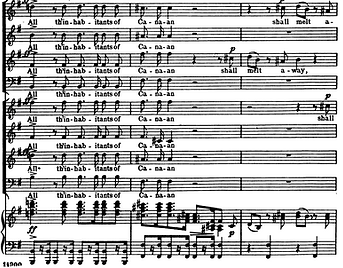

For the meltingly lovely final chorus of the first part of Israel in Egypt, Handel adapts the B section of one of Stradella's arias:

The final Stradella inclusion is a fleeting motive used for 'shall melt' in no.33, which is one of Handel's greatest choruses — one might think it coincidence, were it not for all the other Stradella borrowings.

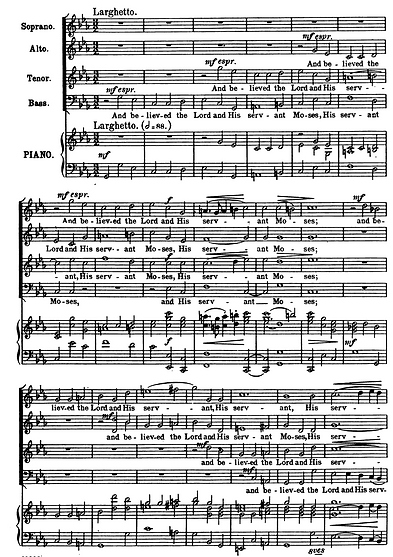

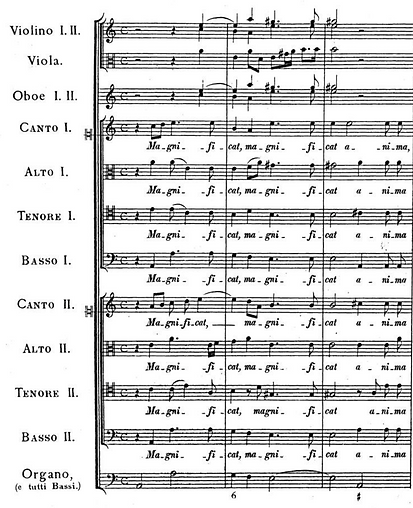

erba's magnificat

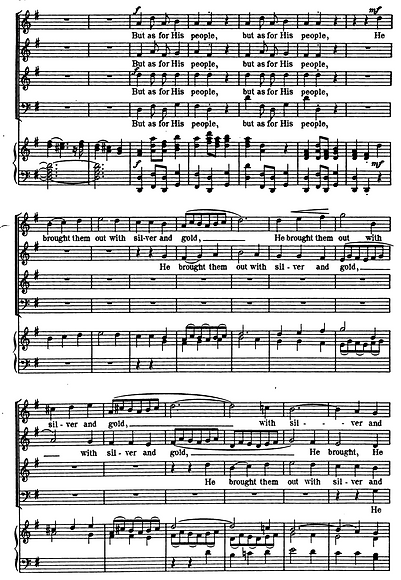

Dionigi Erba, a Milanese composer, is an extremely obscure figure: Grove musters barely a paragraph about him, and he is known chiefly for the double-choir Magnificat which Handel mined so exhaustively for Israel in Egypt. Almost every movement of Erba's work provides material for Handel, nearly all during the second part of the oratorio. My discussion here will follow the order of Erba's work.

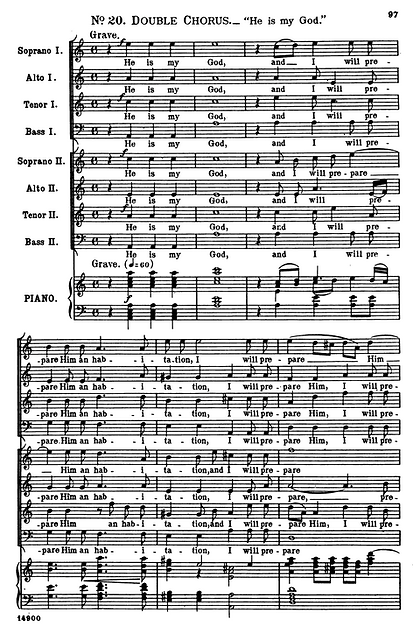

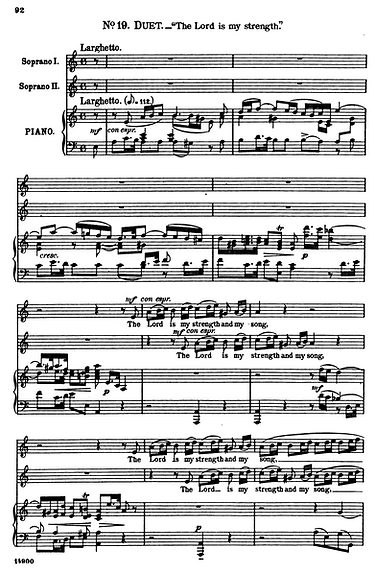

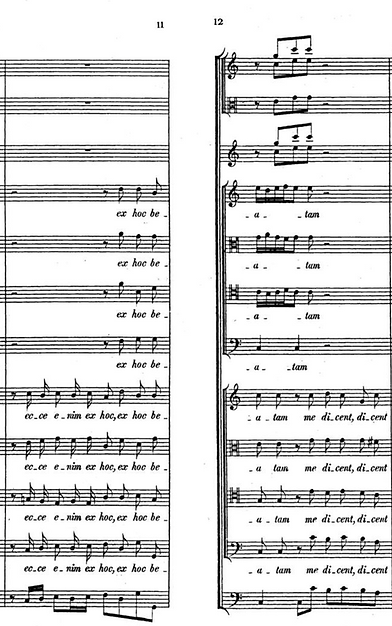

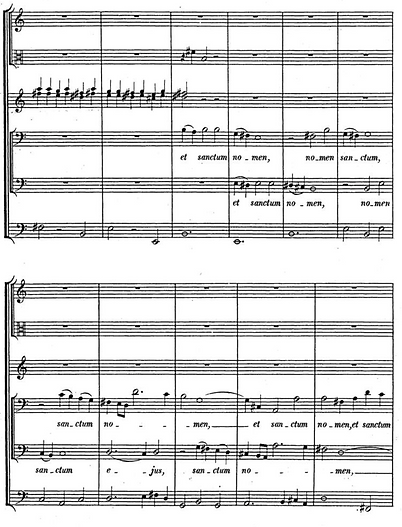

The first movement of Erba becomes Handel's no.20; Handel simply adds two bars to the beginning, and two to the end:

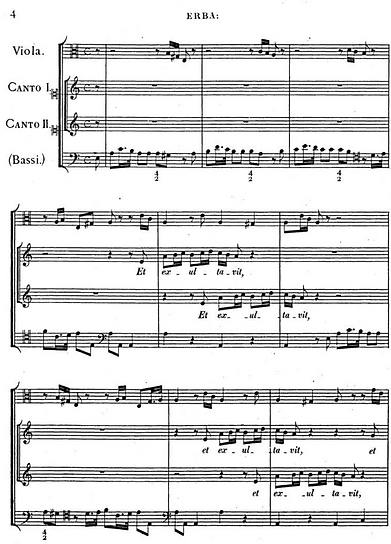

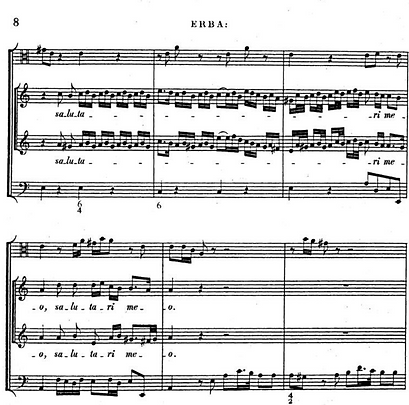

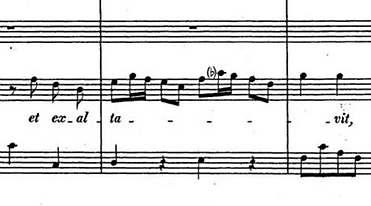

Erba's second movement 'Et exultavit' is a duet for sopranos, which becomes Handel's no.19 — Handel made some additions, but much of the fabric is the same, and there is a striking echoing of text between the Erba's closing 'salutari meo' and Handel's 'my salvation'.

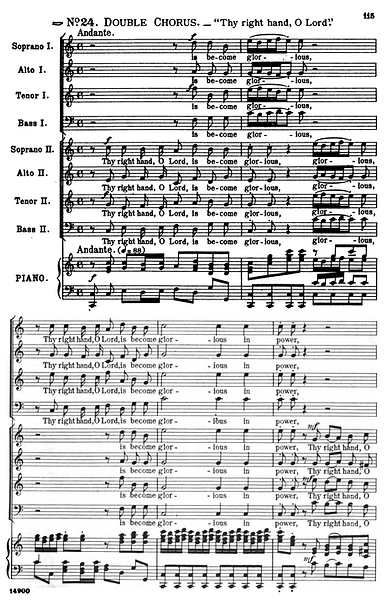

A short snippet from Erba's no.3 furnishes the motivic material for Handel's effervescent no.24:

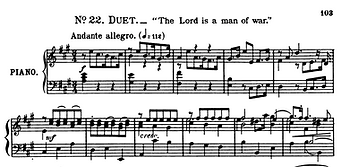

Handel's bass duet no.22 begins with ritornello from a Te Deum by Urio, another obscure Italian composer:

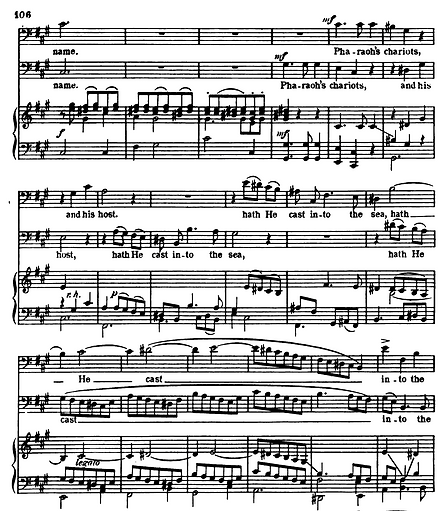

However, a fair amount of the remainder of this duet is drawn from Erba's fourth movement 'Quia fecit'; again, there is synergy between the texts, both of which feature military imagery. A short excerpt will suffice:

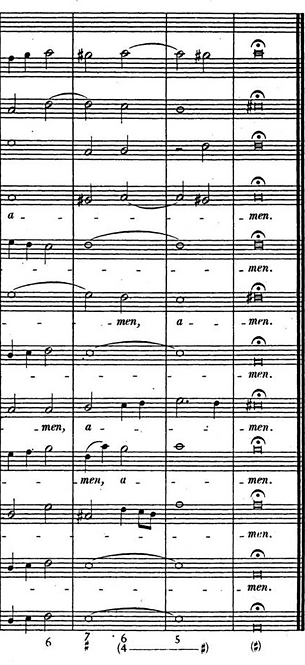

Erba's 'Quia fecit' becomes Handel's severely contrapuntal 'Thou sentest forth thy wrath' (no.26) — again, the texts are well-matched. Handel appropriates the entire chorus, adding six extra bars at the end.

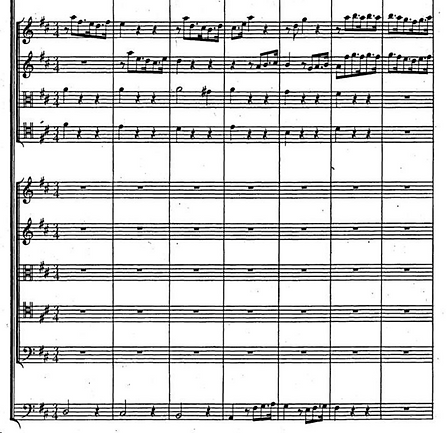

Handel's 'And with the blast', no.27, began life as an alto aria, 'Deposuit potentes'. Its solo origins in Erba can be seen in the various passages in Handel where a single part is featured:

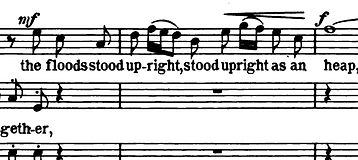

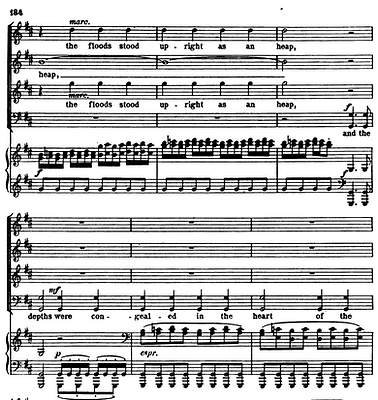

Handel also takes Erba's idea of contrasting high and low phrases to paint 'exaltabit humiles' ('exalted the lowly') and exaggerates to contrast 'the floods stood upright as an heap' and 'the depths were congealed...'

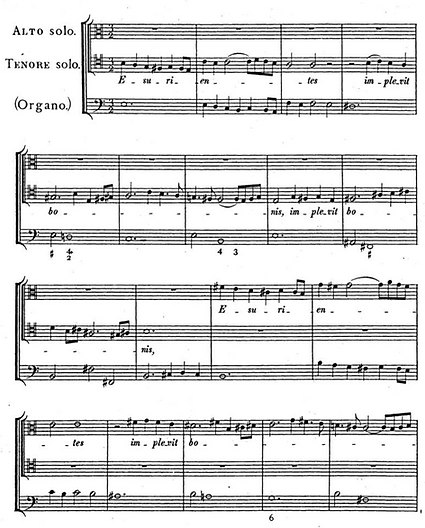

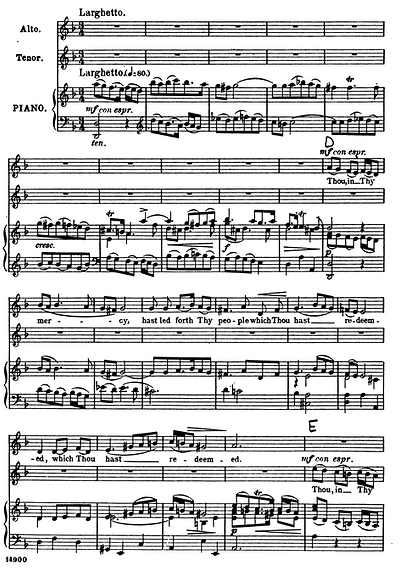

The next Erba movement, the 'Esurientes' duet for alto and tenor, becomes Handel's duet 'Thou in thy mercy', no.32. Once again, the two texts are very closely aligned in terms of mood and meaning. Handel uses almost all of Erba's music but adds a contrasting middle section of his own.

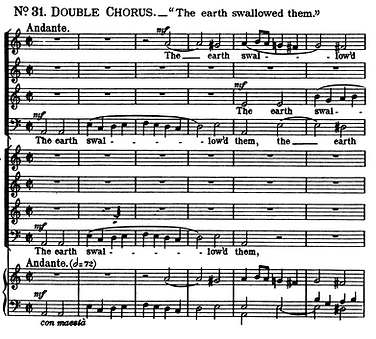

Erba continues with two short movements for double choir and a small tenor aria which Handel overlooks, but concludes his work with a scholarly 'Sicut erat'. Handel takes this over in its entirety for 'The earth swallowed them', no.31,

Surprisingly, the ending to this chorus, with its 'overhanging' S2 part — which feels to me like one of the most archaic things in the piece — is actually the one moment where Handel does not follow his model. Erba finishes in the major, with all the parts resolving at the same time. Handel changes it to the minor, with the soprano moving later, almost as if to underscore the change!

Kerll and gabrieli

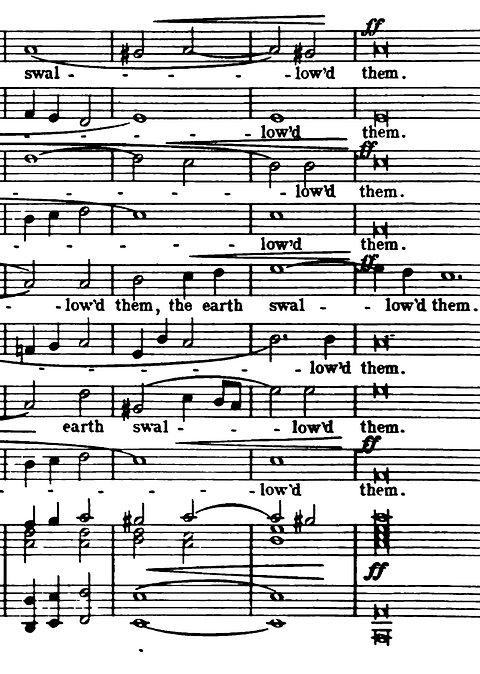

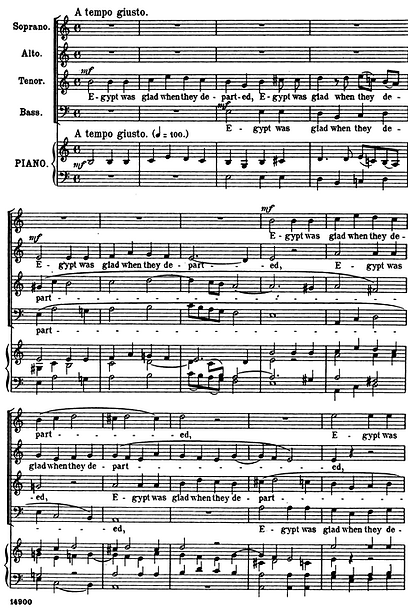

JC Kerll was a highly respected seventeenth-century organist-composer and teacher whose works were studied by both Bach and Handel. His Canzona 4 was transcribed almost unchanged as Handel's chorus 'Egypt was glad'. Its old-fashioned modality and contrapuntal rigour are striking.

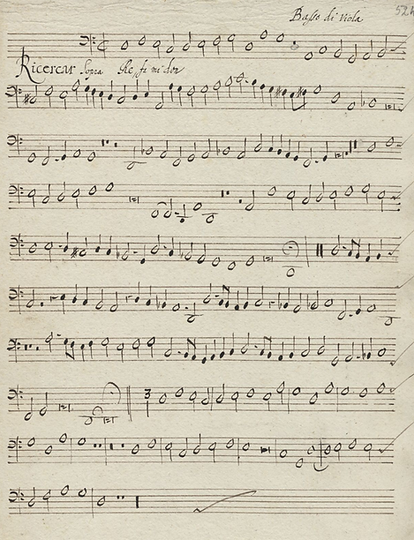

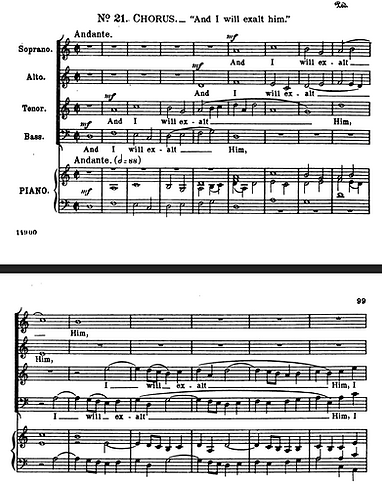

Giovanni Gabrieli is even more stylistically remote from Handel — this is music written well over a century before the oratorio, and it's not at all clear how Handel would even have known it! The Ricercar sopra 'Re fa mi don' survives in a manuscript in Kassel, perhaps associated with Schütz, where it is attributed to the Italian composer. Handel reworks it (fairly extensively) as the chorus no.21 'And I will exalt Him', adding a (very obviously more modern) short section in the middle with the text 'He is my father's God'. I can't find the music in score, so I reproduce the bass part below.

handel borrowing handel

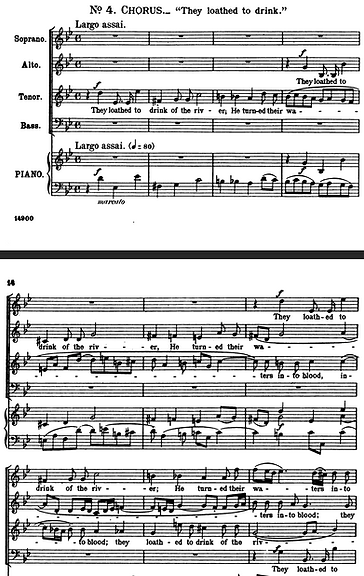

The final group of borrowings to discuss are those where Handel turned to his own music. Two choruses early in the piece are based on keyboard fugues, probably written twenty years earlier. The craggy 'They loathed to drink' (no.4) is adapted from the A minor fugue, HWV609:

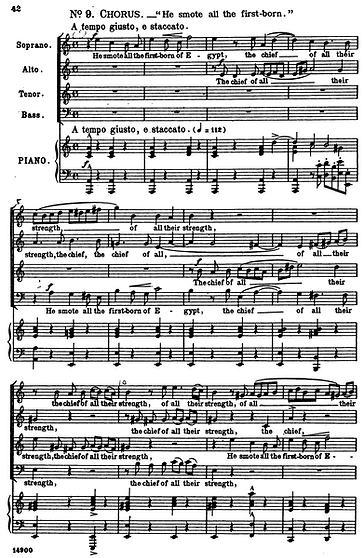

Meanwhile the violent 'He smote all the firstborn' is based on the G minor fugue, HWV605.

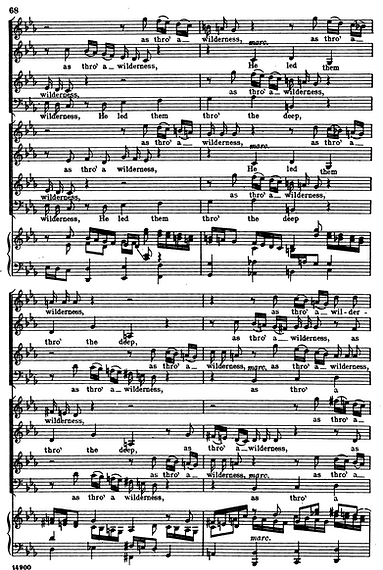

There is a clear kinship between the virtuosic chorus 'Tu es sacerdos in aeternam secundum ordinem Melchisedech' in Dixit Dominus (a work of the early 1700s) and the striding ascending crotchets and falling semiquavers of no.13, 'He led them through the deep'.

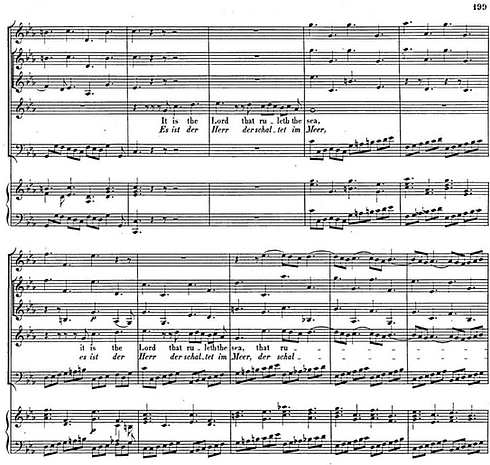

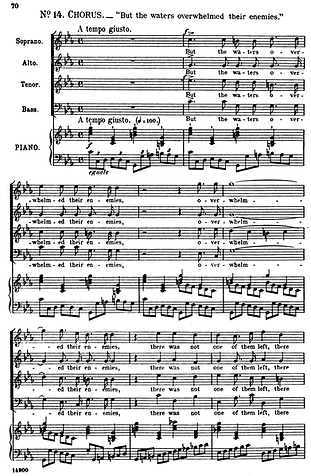

Finally, Handel seems to have borrowed from his early Chandos Anthem The Lord is my light (1717-8) for the rumbustious C minor chorus no.14 which follows: the key, the 12/8 feeling, scale motifs in the bass and octave leaps in the violins are common to both. The link is surely clinched by the subject matter: in the anthem, 'It is the Lord that ruleth the sea / the Lord sitteth above the waterflood', and in the oratorio, 'But the waters overwhelmed their enemies'.